“Limouse and Baudelaire, two beacons drawn to each other by an intuitive phenomenological attraction from as early as 1919, through to the painter's ninety-first year in 1985. Hundreds of drawings, canvases, sketches, ink-and-washes in the space of almost seventy years: that, surely, is an achievement without precedent in the history of art. The University of Oxford was the setting in which the Baudelairean artist's impressive masterpieces stood revealed. Limouse’s brush rendered the poet's brooding melancholy with the grandiose accents of truth, alive to that transcendence which, following on from his illustrious model, he discovered in himself. By turns vehement, excoriating, coruscating and superbly inspired, the painter has brought within our reach lyrical flights of flawless elegance.”

André Weber, 1983

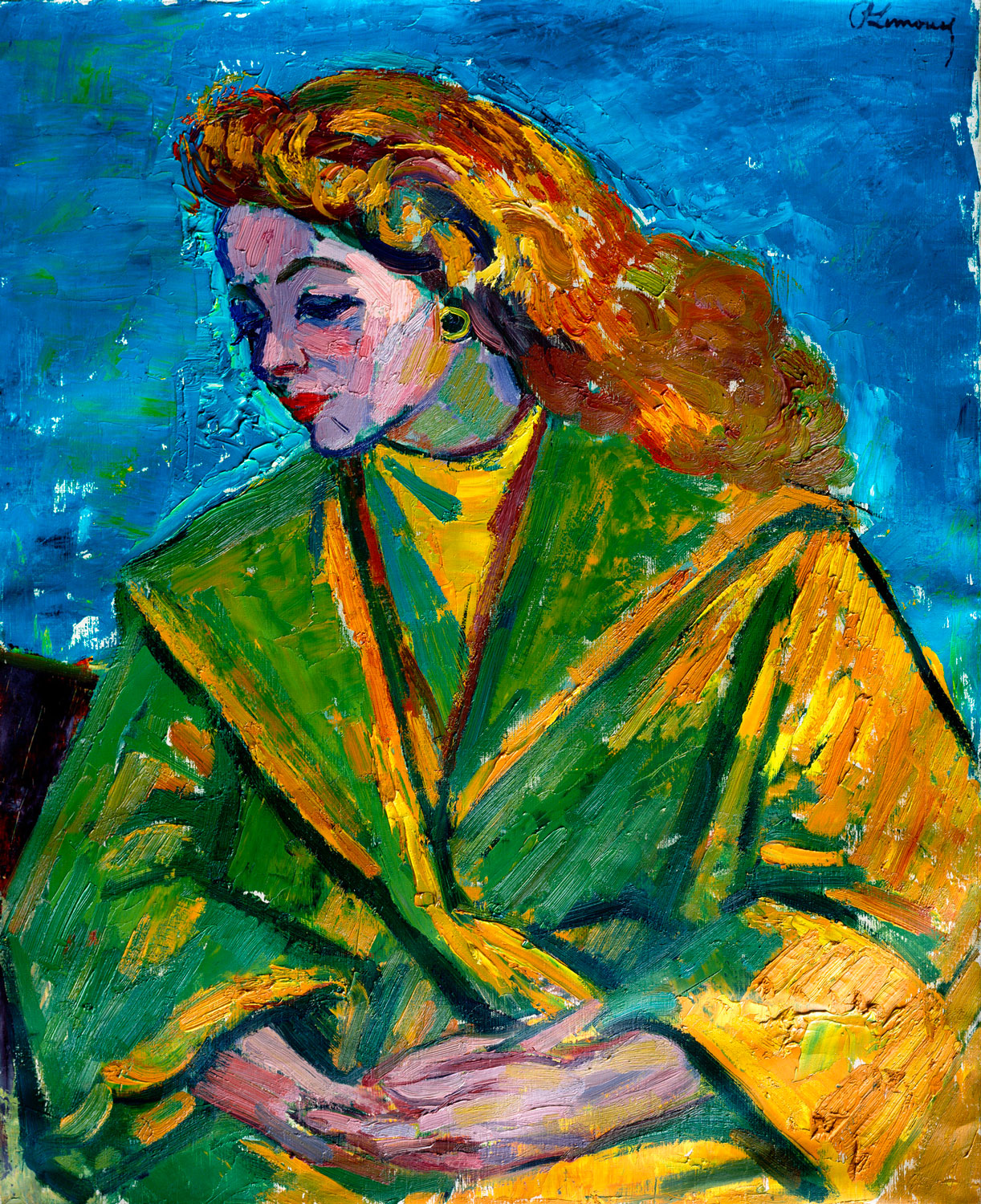

1963, oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm

The Baudelaire Society and Limouse Foundation Ltd Collection

THE SPIRITUAL DAWN

... your all-conquering phantom is as one,

Resplendent Soul, with that immortal sun!

THE SPIRITUAL DAWN

This painting is based on one of the most reverent and idealizing poems that Baudelaire ever sent to his uplifting Muse, Apollonie Sabatier. The related sonnet portrays that contention of which the poet was so aware, between descent and ascent, between the abyss and the heavens, between darkness and light. The duel between those contrary forces is present in the painting no less than in the poem, even though the triumph of light is as evident there as in the final couplet. Limouse, like Baudelaire, portrays a revered young woman seen through memory’s eyes and at the same time sublimed and transfigured into a supernally-resplendent new entity; and he transfigures her in pursuit of the same mystical vengeance that the poem describes, the same determination to counter degradation with indefeasible elevation.

The striking difference between poem and portrait is that in the former a woman is invoked as a deity empowered to overcome the self-degradation of the poet, whereas in the latter the artist-cum-humanist devotes all his skill and imagination and willpower to the apotheosis of a young woman cruelly persecuted during the Occupation. This would be no facile undertaking because, unless he began with the psychically mutilated being he remembered, the apotheosis would not be hers at all. So, even as he battles to raise her from the abyss, she is suffering still. One can see it in the bowed head, in the downcast eyes and the unmistakably pained listlessness of that farther pupil, in the glum hardness and tautness about the tiny rosebud mouth. She looks frail and vulnerable, even actually wounded, despite the protection of that comfortingly thick coat with its broad shawl collar and generous sleeves in which Limouse has chosen to enswathe her.

But although she bears the marks of her hardships and struggles in the material dimension as a contender among the motley horde of mortals, her metamorphosis into a triumphant deity proceeds and reaches completion even as the travelling eye explores this enchanting composition. Gradually, our gaze ascends, through the greens of that ample coat where encouraging highlights begin to appear, and thence the eye follows that breaking wave of chevelure, and rises further still above that radiant mass that brushes the temple, resplendent like the ‘immortal sun’. Already the eye senses that the subject is ‘all-conquering’, and now that carefully managed roll of curls framing the subject’s brow reinforces the consecrating message, for it is the triumphant wreath of a heroine, the tiara of a great lady, the halo of a deity.